'If you work in cities, in landscapes, and in buildings, the medium you work with is alive.'

Hunter Tura, CEO of Bruce Mau Design, on how place branding should learn to roll with revolution

8 minute read / Rosanna Vitiello

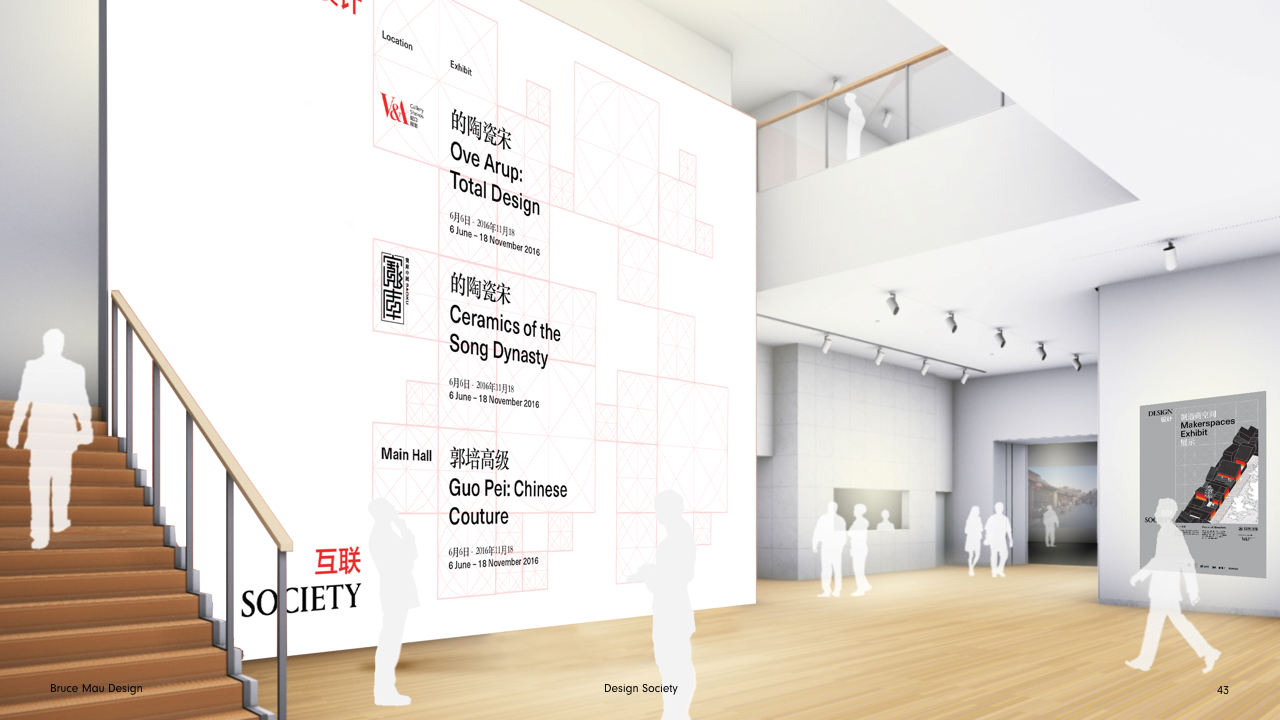

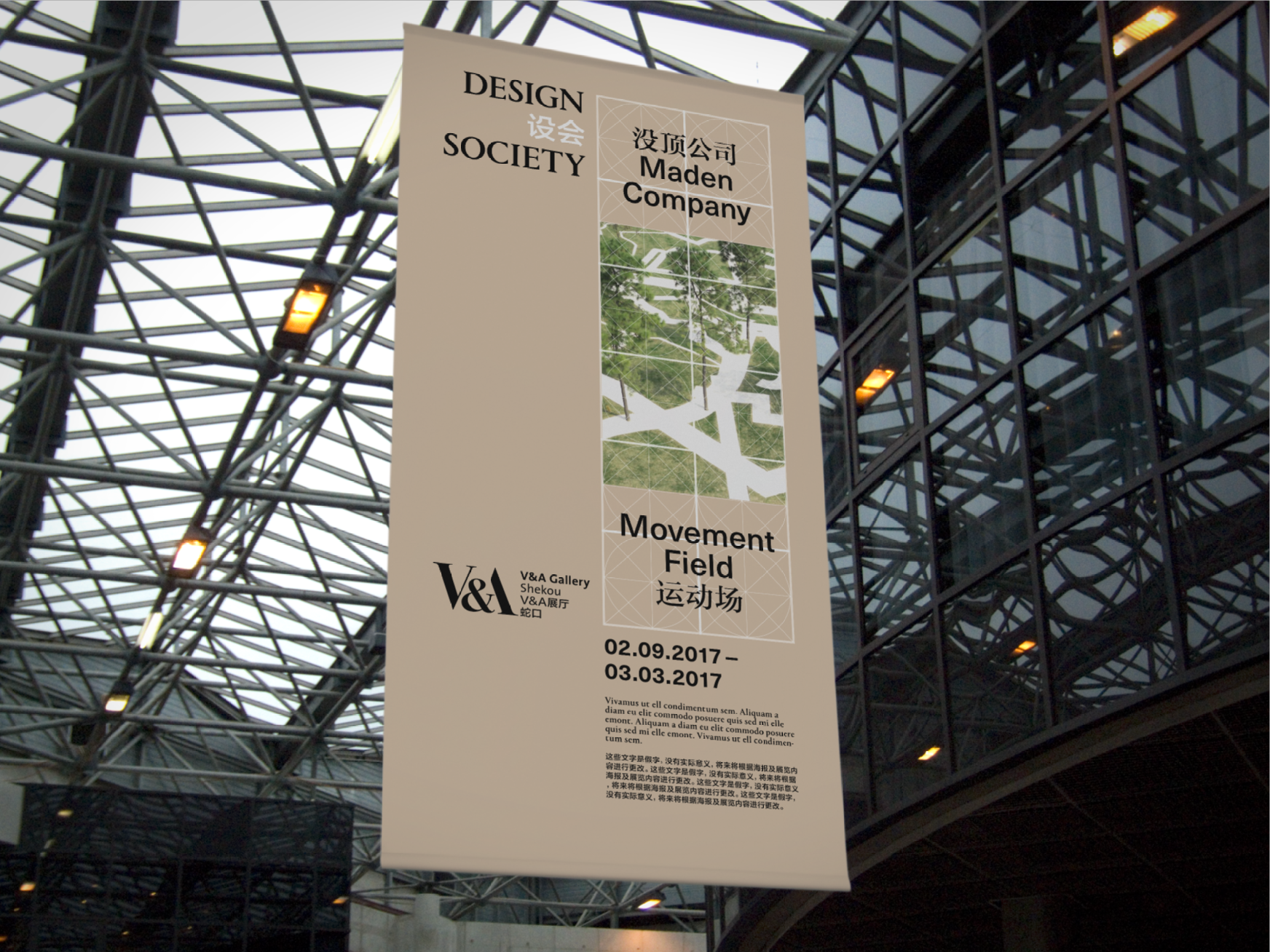

Hunter Tura is the Tarantino of place branding — or so we like to think. Directing the teams at Bruce Mau Design, he’s shaking up the formulaic arena of branding places with a style, intelligence and leftfield wit that’s raising eyebrows and turning heads. This super-charged thinking has opened the door to some radical commissions — from re-imagining the identity of vast nations (Canada) to re-inventing the museum for the 22nd Century (Design Society in Shekou, China for the V&A).

So if there’s one thing Hunter believes in, it’s defying convention, questioning how the field defines itself as a case in point: “We talk about branding the mission as opposed to the place. A higher purpose of creating a civic experience.” It’s this deeper read that sees branding go beyond image to become a platform for exchange, and characterises the studio’s collaborations with world leading thinkers in architecture, culture and commerce — because as with all the best directors, it’s his team and partners who are the true stars.

“I'm interested in the unexpected,” says Hunter. In this era of uncertain national narratives that capacity to roll with revolution might be just what the world is looking for. So we meet at Bruce Mau Design’s New York studio to talk higher purpose, relishing the unknown and working with a medium that’s alive.

Hunter, tell us about your background - why did you choose to study architecture?

Actually, I was originally training to be a historian, studying totalitarian regimes and ideological movements. I was trying to pick up this girl on the first day of school, and at the end of class, she was staying for whatever class was next. I thought that if I stayed, I could maybe, you know, borrow a textbook or something.

The class that I sat in was called Form of the City. It was the introduction to urban form and urban theory, the political and cultural consequences of planning, how you evaluate cities at the human level. An hour and a half later I was completely in love with cities. I've never spoken to the girl again...

And when did you take over at Bruce Mau Design?

Over the 35 year history of the firm, many of the more iconic moments have been defined by collaborations. BMD combines brand and spatial design; these have always been closely linked to key moments of transformation. When I took over in 2010, that was another one of these key moments: an architect taking the leadership of a design firm that had been defined by its collaborative work. It opened up a new generation of potential collaborations for us; we’re working with FR-EE, Hollwich Kushner and others.

-

This whole generation came of age together, and we're able to reinvent the template.

-

I don’t have any training in business, so that’s the part I’ve had to learn on the go over my career. But it means that I can bring the creative side of what I do into how we structure a project and how we put together a team. It’s really useful because it’s not about thinking, “well, you don’t have this amount of money, we can’t work together.” It’s saying, “we want to work together, we want to make an impact in the world - so we’ll find a way to do it."

In your collaborations between architects and designers, what do you see as the differences in approach?

I find that architects tend to take a minor point and start in the middle. But they're really good at synthesising many streams of input or information, and they tend to work collaboratively. In an architectural project, you have to synthesise lighting, engineering, the client’s concerns, the budget, graphic design and signage, and bring it together into a whole. No matter what discipline you ultimately go into, that ability to process simultaneity is an amazing skill. Architectural education is one of the best courses of training in the world for almost everything but practicing architecture!

Designers, on the other hand, tend to work more individually, but they're much better at creating coherent linear narratives. Because they're producing things like books, videos and posters that have to summarise a larger set of ideas, designers are very good at creating coherence and hierarchy within the narrative.

And how does narrative come into your work?

I think the challenge for us, working on brand narratives and urban narratives, is how you get out of the predictable. I've been doing this test recently to see how predictable stories can be. I think it's Chekov who talks about the idea that when a gun enters the story, someone will be shot. That's an incredibly predictable thing.

I'm more interested in those kinds of stories where we talk about the unknown and the unexpected. Obviously, we need a frame of reference to familiarise ourselves with what we're watching. But beyond the fundamental clues for legibility, what can we do that's unforeseen?

How does that work with place brands? How can you create space for the unknown?

Most branding is complicit with the market logic of just putting up the necessary messages to sell something. But just putting a commercial veneer over something, if it’s not authentic, doesn’t drive results or sustained engagement. So how can we create things where people want to develop activities and rituals, where they’re coming back not just to the place, but to the brand in a meaningful way?

-

We talk about branding the mission as opposed to the place - a higher purpose of creating a civic experience. The brand becomes a space for participation and exchange.

-

Know Canada, an identity and campaign for Canada, 2012

For example, for the ‘Know Canada’ project [an identity campaign developed for Kurt Andersen’s STUDIO 360 for Canada in 2012] , we created just two red rectangles and a tagline. Anything was possible within that frame, as long as it was in Canada. People were submitting their own photographs and defining their own image of Canada's brand in the twenty-first century. It went viral on the news, and all of a sudden Ottawa brings us in to talk about the work, to talk about what it means for the future of Canada, and the way the Trudeau government projects the brand of Canada in an increasingly unstable world. I was asked by one of the undersecretaries, “You know, Canada is going for a spot on the UN security council; how can we position Canada's brand for the world to feel like this is someone they want to vote for?” To have a seat on the security council determines war, and peace, and many other critical geopolitics. So a campaign that has a viral life is leading to a conversation about what Canada's role in the world should be.

Another example is Facebook, which is nothing but a brand. There is a sophisticated technology and an algorithm that makes it work, but it is the place you go to exchange photos and birthday wishes and likes and pictures of your child. It's a neutral framework where such an amazing set of activities can happen, including things like the spread of fake news which influenced the outcome of the American presidential election. That neutral framework can produce all of these unforeseen outcomes.

Is that idea especially relevant now, thinking about the current political unrest in both the US and the UK?

It's precisely operating in that unstable set of circumstances that we might be able to provide value. In the absence of clarity of the national narrative, we can help to create moments of identifiable legibility. As toxic as the current dialogue is, it's fun to think about what might come after this. In both cases, the US and the UK, I'm optimistic for a better future.

'Know Canada’, 2012

I know that Bruce Mau Design is opening a London office too. In this political climate, are your Canadian origins important to you?

Bruce has this quote: "The world needs more Canada". And it's true! Canada has to make the case for liberal, democratic, secular, humanist, civil rights in the world.

On the one hand, Canada is a stable place to work. It provides a great lifestyle for the people who work there. It is a calm place. I think we underestimate how important the calm is in the world today. At the same time leading fashion brands, beauty brands, automotive brands, and hospitality brands don't immediately think of Canada or Toronto as the first place for ground-breaking design. They're thinking of Berlin, New York, Tokyo, Amsterdam, London. So, we're really just taking something that we think is pretty special and bringing it to markets where we can reach a wider set of audiences.

Also, Justin Trudeau is one of the few world leaders you see smiling. You don’t see Trump smile. You don’t see Putin smile!

'Know Canada’, 2012

Tell us about your working process. How do you go about developing a vision for a brand?

I believe in processes, not process. If you think about our work branding the first museum of the 22nd century, or a skincare line in the US, or a luxury hotel in Toronto, or a Japanese sneaker - the markets, the consumer base, the channels with which they communicate, they're all radically different. What makes you think that one design process could, or should, organise our work efforts for an incredibly diverse set of clients?

Pluralities drive innovation; they make it more fun, interesting, and dynamic. I love processes, in the plural. I love thinking, okay, what are the things we can do to create something that we don’t know what it’s going to be? It provides a much richer base to start from.

-

I think the role of a designer in the 21st century is not that of an author, who pens the beginning, middle and end - but that of an editor.

-

It's about taking the fragments and the concerns, and helping to bring about an outcome, as opposed to knowing what it is beforehand.

We worked in Asia a lot in the 2000s, and I learned a lot about humility. Designers in the UK and in North America, I think, are trained not to demonstrate humility but to demonstrate expertise. There, I really forced myself to listen first, ask a question next, give my opinion third, in that sequence. I've built an organisation where I'm the least intelligent and talented person. But I have one talent that is better than almost anyone in any organisation, which is that I assemble the best talent. I'm like the General Manager of Chelsea FC. I'm bringing together Eden Hazard and Antonio Conte!

Design Society, a new cultural hub in Shekou, China, 2016

What happens when you’ve developed the vision and you shift to thinking about the design and the implementation?

If you work in cities, in landscapes, and in buildings, the medium you are working with is alive - and that is a super exciting idea. It's also where the brand can become a means of communication, a platform for exchange.

There’s something fascinating about the connection between people and place. And if we talk about people and brand, you want that same connection between you and the brand. I love my Samsung. I want a pure experience; I don’t want the warning message that comes up every morning asking me to install the new Android. It kills it. We need to design experiences where you keep that focus on one another.

And finally, how do you hand the story over? How do you pass on the brand at the end of the project?

Ideally, the institution or the product or the place becomes the brand. I don't want to be constantly pushing out campaigns. I'd rather that the life of the place becomes the experiences there, or the product becomes the enjoyment of the juice.

I was at the Kennedy Centre the other night for the Gala, hosted by David Duchovny. He was hilarious. Steven Van Zandt, Amos Lee and Esperanza Spaulding were performing. That was the set of stories that I came away with. The logo and our typographic choices are just the things that frame all the stories that are going to come out of a really dynamic institution.

If you were to give one piece of advice to placemakers on how to use narrative to make better places, what would it be?

It’s not only a design thing. Do less to create more natural conditions where the unexpected can occur. If you’re really that smart, you have an obligation to make it clear. That is your role as a designer. Make it something that people can understand and experience and make sense of.

LEARNING FROM HUNTER

Brand the mission, not the place

Places are living breathing platforms for participation — and with that comes a host of unexpected events. It takes a leap of faith to handle the unknown, but Hunter’s approach moves a place beyond being seen as a ‘product’ to an active agent for change that brings people together.

Un-predicting the future

Placemaking and branding inherently consider the future, but no-one enjoys a predictable story. So get ‘Chekhov’s gun’ out of your system, think of the obvious, then dream up the opposite to deviate from the norm.

Sparking something meaningful

The best brands spark movements. So when the focus of a brand centres around a place it has the power to galvanise change among millions. From swaying a nation’s reputation and international relations, to unifying citizens in uncertain times, ask ‘What is the movement this place can ignite?’

Keeping it alive

Many place brands aim for clarity but end up with rigidity — an approach means they’re ill-prepared for the future. Embrace the idea of working with a living medium and make the space for others to evolve that brand for it to truly come to life — as Hunter states: “I’d rather that the life of the place becomes the experiences there.”

Want more?

Catch Hunter live speaking at the London Design Festival at the V&A on September 17th.

Or follow BMD’s work at brucemaudesign.com