'How can we shift perceptions of culture in Essex?'

Focal Point Gallery Director Joe Hill on challenging place narratives

8 minute read / Rosanna Vitiello

Essex is a place of extremes. Love it or hate it, we’ve all got an opinion on it, and it’s a point of view that Joe Hill sets out to challenge. As the Director of Southend’s Focal Point Gallery, he brings a daring perspective to his seaside surroundings in the perfect place to discuss narrative — a hybrid building that houses the town’s library as well as the gallery.

Focal Point Gallery’s approach is rooted in Southend and the gallery is an Aladdin’s cave of stories connected to the county. Joe’s passion for the place resonates through the anecdotes he serves up — from the history of Canvey Island to mythical artworks embedded in the building’s walls. His commitment’s clear: “I couldn’t not live here,” he explains, “you’ve got to fully immerse yourself in the cultural fabric of the place.” So while the gallery’s door is always open, their programme remains uncompromising and experimental. Among their boldest moves is the Radical ESSEX project, partnering with Visit Essex and Essex County Council, which delves into the lesser-known modernist architecture and social heritage that have shaped the county. The project takes a critical view of the culture and asks: can we uncover an alternative narrative for Essex? Can we shift perceptions of the place? And now we know more about its radical roots, can new ways of living find their test bed here?

Do you think Essex has always been a place that's aspirational? Or optimistic?

I think historically it has. In the early part of the 20th century, there was this big push, particularly out of East London, into parts of Essex to make a better life. That relationship was about being connected to nature; then came the New Town movement, when it evolved to become about better places to live, and a more utopian vision of life in the community.

And I think now you've got another wave happening. The creative communities that live in London are unable to stay there, so they’re looking for options outside the city. We have been at the bottom of the list in some ways, but people are starting to realise that there's an interesting story in Essex.

—

Artists and creative people always want to live somewhere where there's an interesting story. They don't want to go somewhere that doesn’t challenge their perceived way of living. Artists like to be in the middle of something.

—

The activity here is optimistic, and what comes out of the county appears optimistic. I'm not sure the people are always optimistic about themselves and their ability. It’s embedded in the stereotype. You get a lot of people who've done well, saying things like, "I'm just an Essex girl, done good."

I come from Yorkshire, which is the complete opposite. People are incredibly proud of their heritage and their history. I always get interested in how Essex people talk about themselves and their success. Because why shouldn't somebody from Essex do well?

Tell us how the Radical ESSEX project came about.

It's an interesting move because Focal Point Gallery has always prided itself on being rooted in Southend. We rarely take touring exhibits because we want the work to originate here. It has to have a relationship to this place. Otherwise we don't want to do it, because we see our purpose here as bringing in new voices to reflect on this context.

We'd been looking at a few interesting historical projects nearby. One was the Plotlands settlements, which is a community of self-built houses that occupied the land that Basildon New Town was eventually built on, and also the Bata Shoe Factory and the incredible story there.

We were given the opportunity to lead a project funded by VisitEngland and the Arts Council, called Cultural Destinations. It’s a project aimed at building networks and relationships between cultural organisations and the tourism sector, to challenge the cultural perceptions of a place — in this case, Essex.

This gave us the opportunity to build on our research and explore a new narrative of 20th century radicalism. That then opened a floodgate for us to talk to people, and make connections with writers and those who have been interested in this angle.

We'd also been interested in some of the early experimental modernist architecture in the county, like Bata in Tilbury, Silver End Village and Braintree.

—

We started to paste this narrative together and it made total sense.

—

Why do you think Essex was this hotbed of radicalism?

I've got a few theories about that. There's a writer, Ken Worpole who describes the communities from Essex as a product of extremes. They’ve expressed both politically right-wing and left-wing tendencies at the same time, and therefore, in-between, anything can happen.

There was cheap available land here, and the natural environment as well, so people could get out of the city and grow their own food, and develop their own lifestyle. The area isn’t dominated by large landowners with big estates. And it’s not an easy place to farm. Farmers here have struggled to make the land profitable, so they were looking for new opportunities to do so. If you look at Essex, it has all these rivers that permeate it, and it’s difficult to make transport connections across the county. I was interested in industrial identity here, because you see that in other parts of the country: In Cornwall, you've got tin mining and fishing; Yorkshire is textiles and coal mining. Whereas there's nothing for Essex. It's a non-space, with little pockets of things, not a means of production that has defined an identity for the place.

Those disparate factors leave you with a few key things. One is an abundance of open cheap land, so communities can easily come out here and experiment. And then there's no big landowner controlling the land and defining what's going to happen on it.

—

There's a psychological shift in people if they know that land is owned by everybody, not owned by a single person.

—

Bata Factory, Essex — Catherine Hyland

Within that story, who do you think are the protagonists?

The Plotland movement is important here. There are a number of examples of Plotland communities. Jaywick is one, Canvey Island and Langdon Hills. Thousands of houses that were built by people, essentially, of their own free will, with no planning restrictions and no building regulations.

Then the Basildon Development Corporation redefined the county in the middle of the 20th century, as a key commuter belt to London. The story is tragic, because the town was built over the top of one of the Plotland communities. The Plotlanders were all given places to live in the new town, but many of them kept returning to their Plotland house. In the end, all of the Plotland homes had to be demolished to stop them going back. Today there is only one house that remains, as a museum at the Essex Wildlife Trust, in a place called Laindon Hills.

—

I got interested in these two types of utopia: the social utopian vision of the Plotlanders and the imposed utopian vision of the new town developers, that was like, “We know what’s best and this is how you should live."

—

They gave propaganda out to the Plotlanders to say, “This is your new home.” There was genuine hope in those projects.

In the latter half of the 20th century it’s been dominated here by the commuter stereotype: the aspirational banker who works in the city but lives lavishly in the suburban cul-de-sacs of Billericay. It’s people’s image of the place, and it’s a really ‘young’ stereotype. Other parts of the country have stereotypes that go back much further - if you look at how the industries of growth in Yorkshire defined its stereotype, that has been there for over 150 years.

Whose role is it to define or redefine the story of a place? Should it be undertaken by tourism bodies?

I think the tourism bodies do need to be mindful of this, but it’s hard because although they appear to be publicly funded, they are often only part-funded. The majority operate through a membership scheme business model. Allegiances therefore must lie with the members, and with narratives that promote their businesses and activities.

On beginning our conversations with Visit Essex, this was a hurdle that we needed to get over, but we all soon realised that this was going to be about educating both sides. It’s about ensuring that the cultural sector understood how tourism worked and how they were currently driving people into the county. The tourism sector can learn how culture can play a role in that, and that some of those stories don’t need to be purely commercially-led to bring people into the county. Then it became a journey: “Well let’s test this, let’s try this and we’ll look at the outcomes.”

Flood House Commission, Southend Pier

How did the press play a part in it?

The press interest was fascinating. If you can present a different story of a place...the amount of people who want to write about that! People doing various things at the ESSEX Architecture Weekend, coming to the exhibition and other activities - it genuinely shifted their perception of the place.

Then there are other things, like people who had lived in Silver End going to Frinton for the first time and seeing how that place got recognition for its Modernism, while Silver End hadn’t, and residents learning about histories that they didn’t even know about. All the internal movement of people around to get to know different stories in different parts of the county.

The north and south here are almost completely different places. The way that the road and rail systems have been set up has also divided the county in two. One thing the project wanted to do was to try and bring people from the north and south together. That’s why we had buses connecting Silver End (in the north) and Bata (in the south).

Now that you’re going to begin the second part of Radical ESSEX, what are you hoping for?

The key is that the network is really strong. The first part was about setting up a strong group of people from different industries: the tourism industry, local government and the cultural sector. The second part is about ensuring we strengthen that and continue to work together. In Essex you’ve got two unitary authorities - it gets a bit complicated!

We’ll also grow that network. We have new partners joining, like the University of Essex. We want to work with the transport system in the county as well, to use that as an opportunity for commissioning and seeing the commuters as audiences for culture. We’re looking at making commissions for the train companies, with content that has geographical specificity: pieces of work that last for periods of time between getting from London to Southend or London to Colchester. We're also trying to do a large commissioning project with artists working across the airport, which would be exciting.

The idea of the Radical ESSEX project was to be county-wide and tell a cohesive message for the whole county. So it’s also about continuing to do that: we are talking about Southend when we're talking about Colchester and vice versa.

ESSEX Architecture Weekend

What’s been the best method of connecting with people locally?

It was actually getting people out into these different places through the ESSEX Architecture Weekend: opening up people’s houses and opening up communities. It was empowering for the people actually living in those communities. For example, a place like Silver End, which some people would think of as run down ex-social housing —

—

People there were saying, "Oh my God, I didn't realise my house was so important.”

—

The best one was Cressing Road, near to Silver End, on the outskirts of Braintree. The estate is a series of concrete block houses that are quite run down. But there's a set of two houses there that are supposedly the first Modernist houses in the country: these concrete block houses that are flat roofed and painted white. We managed to open up one of the houses for people to visit.

The resident came to Silver End in the evening and said, "We've had such an incredible day.” They didn't think people were going to come, and they'd had hundreds of people come through the house, talking to them about what it means. That's amazing.

So is there still a focus on architecture in the second part of the project?

We want to do another rendition of the ESSEX Architecture Weekend and take a new theme. The themes we're looking at this time are the New Town story, but also some of the amazing building projects that are happening around the natural environments in Essex. Things like Wallasea Island, which is this incredible island being built out of the material coming out of Crossrail. They’re pulling this substrate out of London and shipping it down here and they’re building a massive wetland - the biggest in Europe.

We always wanted it to be a lobbying exercise as well, to spur the local government towards clear thinking about:

—

''How do we build in Essex? How do we build communities for the future?"

—

All these councils have a remit to build thousands and thousands of houses; how can we learn from some of the 20th century experiments and bring that to the fore in Essex? The county's actually got an incredible reputation for things like green energy and recyclable practices, so how can we bring some of those stories to the forefront?

Overall, in the new narrative of Essex, what role do you think that arts can play?

Oh God, that’s a difficult question! For me,

—

If the cultural activity of a public institution isn’t relevant locally, it’s not being critical of what’s happening locally. We've actively tried to be a critical voice on the role of culture as a regenerative agent.

—

All of our projects on the High Street, and a lot of the ones on the screen outside the gallery, have taken a critical view of this idea that culture is always the answer. You see that for a lot of councils, and particularly in seaside towns, culture is the new attraction. It’s replaced the arcades and the theme parks. But often, it doesn’t have that critical voice.

I’m interested when people can involve artists in all stages of the process. For example, we were working on public art commissioning in Shoeburyness, at the end of the rail line. It’s got some communities that are at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum in Southend. We're working in a number of public parks there, thinking about how public art can play a role in this. One of the artists that we were working with made suggestions on all of the design processes - things like, when you redo the tennis courts, why not do them in the same colours they use in Wimbledon or the US Open, so that there is this aspirational feeling to people playing on them. Suddenly, even though we're doing a different commission with him, he's become a consultant resident artist in the process with the councillors and with the council offices, which is fascinating.

And then the other artist we’ve commissioned there is working with the people who use the park, developing a skills-led programme where they will learn to build an actual structure that they'll design and work on with him. The young people and the schools are involved, and different social groups.

—

I think artists can be fundamental if you think about how you can work with them differently.

—

We talked earlier about the aspirational or optimistic nature of Essex. I think generally people in Essex are not optimistic enough. But sometimes that allows them to be incredibly open to different ideas and innovations. It’s almost like you’re starting from rock bottom, so you can go anywhere! I think that's not good, but it does mean that the place is open to different types of ideas and different ways of thinking.

Southend Railway Bridge Commission, Mark Blower

What’s your hope for Essex?

I'd love to be a test bed for new ways of building, new ways of living, constructing communities. And to be a culturally vibrant place - the place that supports artists and musicians, supports creative people to live and work.

I go to quite a lot of meetings about how you develop Essex from a business perspective - culturally, building, place making all that stuff. I always say:

—

Please, please, please be innovative and be experimental.—

I'd love to be the point at which we could do some experimental housing projects, like: how can we build for the future? Seeing Essex become a test bed for new ways of building, new ways of living, constructing communities, and taking that as an influence to work politically. And to be a culturally vibrant place - the place that supports artists and musicians, supports creative people to live and work.

On which note, Joe takes us on a walk around Focal Point Gallery...

Joe Hill talks us through the Volker Eichelmann show

Tell us how you go about selecting projects for the gallery.

There's a couple of strands that we always try and think about when we consider who we're going to programme for the gallery. One is our position in Essex. We have a term that we call "rooted in Southend." So we want the projects to have, at least as their starting point, the context of where we are.

We're also interested in how the digital arts play a role in telling that story. So we do a lot of developing narratives through digital work. The other thing is our relationship with the library, because this building is also the main public library. So we're interested in printed material; we've produced a lot of our own printed material, but also artists who have worked with the idea of books, and book making, and printed matter.

What’s the latest exhibition?

A project that we've been working on with German artist Volker Eichelmann responds to the ornate gardens of Southend’s famous seafront. It also includes the work of Stephen Tennant, who was one of the bright young things prominent in London in the 1920s and 30s. He was particularly famous for celebrating early trans-culture. He’s also credited as being one of the earliest celebrities: he would go out and be photographed in London, and people would follow his movements through the newspapers.

He made a series of book covers throughout his life for these books of poems he was going to produce. But he never managed to actually publish any of them. So these are an unrealised project. One of the key artists who’s interested in Stephen is Volker Eichelmann. We’ve developed a project together where we could show some of these amazing Tennants, but inside a sort of giant collage that Volker has made.

It's an interesting connection between the past and present of Southend.

Definitely. We talk a lot about Stephen and his relationship to Southend, and what that would have been. But Volker’s interest was in the Victorian seafront as well, and in the idea of the folly - the production and design and building of a folly, which is a ridiculous undertaking. It's similar to some of Tennant’s work, where he started things, and never finished them. Volker’s been filming and photographing follies all over the world. The exhibition is called On Peacock Island, which is an island on one of the lakes just outside Berlin; it's full of follies and peacocks.

The way that Focal Point Gallery promotes itself always seems really vivid.

—

We're a regional cultural organisation, but that's not a reason to compromise.

—

We don't want to do something watered down; we want to help people to engage with the language of contemporary art, and cultural activity more generally. I don't think you need to make things more conservative in order to do that. So we’re celebrating colour and design.

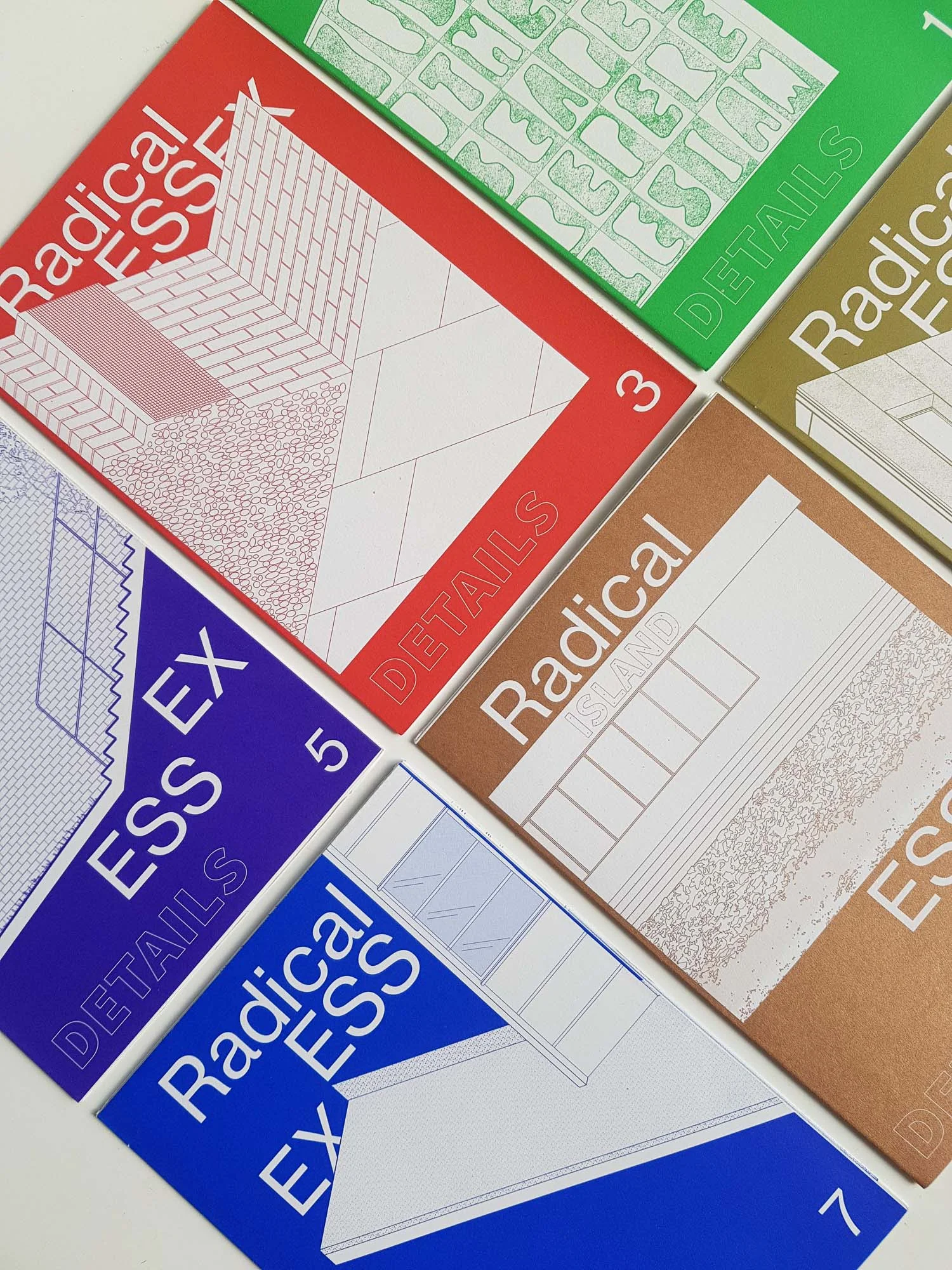

Really, the way the gallery promotes itself stems again from the relationship with the library. Every invite we make or every booklet that we make gets a number, and it's developing into a sort of archive. And maybe that is because we're regional - a lot of the people we communicate with through those methods, or through invites, or emails, may never come here. But we want them to have a sense of what's happening here, wherever they are. So what we send out is as important as the shows. We want a bit of the project to go to them.

How conscious do you have to be of promoting an image to get people to listen?

When we began the Radical ESSEX project, the design of it was critical. We actually made a font specially for it with designers Fraser Muggeridge studio. We realise that not everyone's going to come here. That's just too optimistic. But if we can send a bit of what we're doing here to them, then they can still keep a connection with what's happening. You're making a narrative of somewhere that they've never even been to, which is a perception, isn't it, really? That was what the Radical ESSEX project was set to change. It was about, "How can we shift perceptions of culture in Essex?" The gallery's trying to do that constantly, by making relationships with things in itself, and things in the place.

Radical Essex identity, designed by Fraser Muggeridge Studio

You’re also very much part of the town centre here.

Yes, the gallery windows and neon sign remains lit all night, so it's always open. Again, we’ve done projects that relay the big screen into the window space as well, so we can formulate that relationship. We built two waterfalls in the entrance which are part of Volker's show, people can watch these even when the gallery is not open, to get a sense of what's happening inside.

We start to break down that myth about what's going on in the gallery. We have a project space that can be a bar at openings, a space for talks and events, for education classes, after-school trips and art clubs. There is always something different, people are able to wander in and find something new.

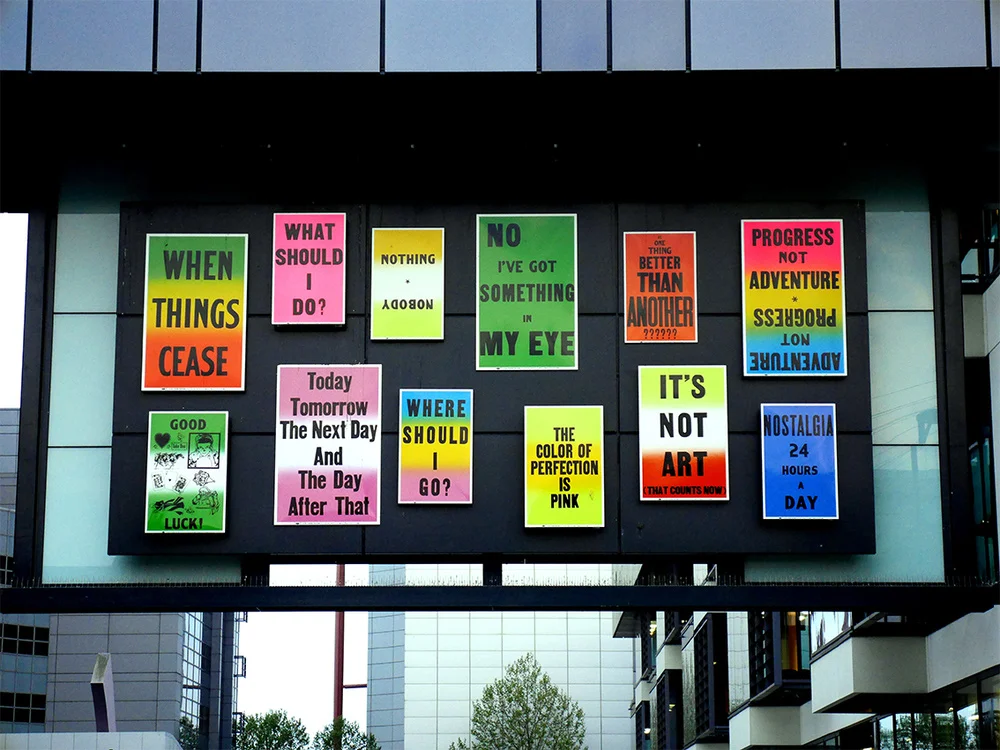

“Progress Not Adventure. Adventure not Progress” states the Allen Ruppersburg commission in the public square outside. In its rediscovered spirit of radicalism, can Essex defy that statement and have it all?

How important is that sense of localness, and those local connections?

The previous director did a great job of building up the profile of the organisation with peers and art world professionals. When moved into the building we are in now, we needed to build on that reputation and make it relevant locally. I took over just before the move. While we're not compromising on the programme, we need to do a lot more work to ensure the gallery it embeds itself and is relevant.

—

We may have a great reputation out of the town, but if people who live here aren't coming, then it's pointless.

—

One important thing is that the council's incredibly supportive. We've worked hard on helping them appreciate the value of culture and what we do. We had the local MP here last week and he'd never been to the gallery. He initially said, “Why are there no local artists showing here?”

I said, "That’s one perspective. Let me tell you my perspective. We want the people of Southend to have uncompromising access to the same quality of shows you might get in London or in other cities.” I feel it’s their right to have that cultural conversation happening on their doorstep. The other point is that if we all had the perspective that he had, then no artists would move around the country at all. They would be just showing in their own local towns. It’s important to find a mechanism to use what we do to support the creative community here. But it’s also important to bring this diverse range of voices in. And suddenly, he’s now our biggest fan.

It’s about introducing people to what we do and why. There's a lot of myths about places like this. One great opportunity we've got here is that we’re part of the entrance to the library. All of those barriers round entering a museum, half of them are already gone.

What projects have you done that you think have helped to build that narrative?

We commissioned Mike Nelson to do a permanent commission. He got interested in the books in the library - in how they were having to get rid of a lot of books to move into the new space. We got him access to the decommissioned books. He then selected 530 of them, and we installed them in the cavity walls at the gallery - a secret installation between the walls of the gallery and the library, which no one could gain access to as it was plastered in. There's even a desk in there and a chair from the original library. Then, we produced a book which is every cover of the 530 books, front and back.

It was funny, me having to stand up in front of the council, and say, "We're going to commission a project that you're not actually going to be able to see."

—

Mike wasn't interested that people might find it in years to come. He was interested in whether people even believed it was there. In the idea that the commission might not exist physically - it might only exist in someone's imagination. In 20 or 30 years, it's even more mythical.

—

But the librarians, some of them cried when they saw it. It's amazing. I think it's because people have very intimate relationship with objects.

What are your ambitions or your hopes for the future of the gallery?

We've got goals around supporting artists to come and live here, as well as supporting the artists who are already living here. We're trying to build a studio block with low cost artist work spaces, and provide the infrastructure that will ensure that people can make work here. There’s a great opportunity for artists to be based in Southend, because you’ve got that really close proximity to London. You can still keep a connection with what’s happening in the capital. But there is an abundance of good housing and spaces to work as well, not to mention a wealth of materials to use in your practice.

Again, it’s the idea of extremes: artists like to exist within the middle of those extremes. Just saying to people, ''You’ve got that here” may not always be easy, and you may have people who are critical of what you’re trying to do. But actually, that’s where we can pull and push, and things can spark in the middle.

Learning from Joe’s Approach

EMBRACING EXPERIMENTATION

Local doesn’t have to mean low-key. If we can learn one thing from Radical ESSEX it’s that focusing on a local context can give us licence to test and push boundaries — sparking interest and painting a new picture of a place on a much bigger stage.

Never compromise on culture Joe’s team don’t water down their work to guarantee mass appeal, believing instead in the eye-catching and the celebratory. This ambition and confidence attracts world class artists and critics to work in a region at an intimate level, while inspiring locals and elevating the place’s reputation.

Keep up the critique ‘Culture’ can fall into a trap — tourism’s new version of a theme park or amusement ride to attract a different audience. But it needs to remain critical to remain relevant. Focal Point Gallery’s ‘Rooted in Southend’ principle ensures that the gallery homes in on site specific and local through a variety of angles and voices, ensuring a richer, louder picture of the place.

Empower change If you don’t like your story, change it. Essex has had its share of loud voices and dominant characters — but as Focal Point Gallery’s work discovered, they only presented one side of the story. Involving creative minds in placemaking has shaped an opportunity for the community to spark new pride in their origins, and create a real change that people feel confident in. Enabling residents to experience their turf in a fresh way can empower them to interact with it in new, productive ways.

Integrate to influence Radical ESSEX’s network has the potential to extend to all walks of life — from the library, to the airport and the train network; from politicians, to tourist boards, and to developers. Culture needs to integrate to influence, changing not just perceptions, but radically shifting realities. That’s the only way to inspire and build an alternative future for a place.

Want more?

Focal Point Gallery is just 100 yards from Southend Central Station, with trains to London every 15 minutes — a worthwhile trip to the seaside.

Focal Point Gallery’s Volker Eichelmann exhibition continues until April 30th; and you can follow the fun at Radical ESSEX here. The gallery’s next exhibition, ‘Maximum Overdrive’, opens 20th May, an ambitious project that seeks to connect the gallery space to its immediate social context at Elmer Square. Artists, practitioners and community groups are invited to activate set perimeters designed by the gallery, mirroring the role of the square as a challenge to how the gallery space can support and network a wider sphere of social or cultural activity with different modes of technology.

Radical Essex is led by Focal Point Gallery in collaboration with Visit Essex and Firstsite, Essex County Council, Southend Borough Council and Colchester Council. Supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England it forms part of the country wide Cultural Destinations programme, a partnership with VisitEngland, supporting arts organisations to work with the tourism sector to deliver projects that maximise the impact culture has on local economies.

And if you don’t make it to Southend, Focal Point Gallery will bring Essex to you — sign up to their mailing list and stay up to date will all they have to offer!