‘The story has to have high stakes. It has to have consequences, or people don't care.’

Radio maker David Waters on tuning into a changing community in Hackney Wick

8 minute read / Rosanna Vitiello

David Waters hears places in high-definition. A radio-maker who layers skills from music and journalism, he brings a crystal-clarity to sourcing the sounds and stories of spaces. David makes audio an artform, creating work that feels genuine, intimate and intense. Although his soundscapes start out subtle, they soon captivate — close your eyes and he’ll take you there. It’s this talent for capturing a sonic sense of place through powerful storytelling that fascinates us — an underused tool in the often tangible and visible world of placemaking.

Commissioned by the BBC, The Guardian, Detour and Airbnb to make audio walks and radio documentaries, as a journalist he seeks people and places with something to say. From the experience of solitary confinement in American prisons; or London’s Smithfield Meat Market in all its gory; and out to the fringes of the capital to document the human side of epic change in Dagenham. We take a walk with David around Hackney Wick, East London, where he’s drawing out stories of the neighbourhood’s creative culture from among the warehouses, and ask — how can the power of audio give voice to a place?

Tell us about Hackney Wick - why are you working here?

This was a big industrial area; then business slowly decayed, and in the '90s a lot of artists started moving in because there was cheap accommodation.

But this area is in flux at the moment, with the Olympics and the property developers moving in. So there's a real fight at the moment between the artist community and the developers: how can this area be affordable for artists to continue to work here? And that's what my piece is about.

This is one of the stops on the piece I'm making. It's the former site of the Lord Napier Pub. It used to be a gin palace. The photographer David Bailey's grandmother used to collect glasses in this pub. She was paid in gin. Then it closed down and it became one of the free party places in London where people used to go and rave after-hours. And now I think it's being developed, and being turned into a pub again.

It's a difficult story to tell because it's a gentrification story, and gentrification stories can be really boring. But it has high stakes, because this whole artist-led development approach is being used all over the world and nobody's managing to pull it off successfully. Usually the artists are kicked out.

Here they're having some success. New art studios are being built, and it looks like this area might be a model for other cities around the world.

What makes a good story?

—

It helps when the story has high stakes.

It has to have consequences for someone, or people don't care.

—

Here, for example, there's the stakes of what will happen to the artists, what will happen to the developers, and what will happen to other cities around the world? Can they develop in a way that doesn't kill fun in interesting places, but also encourage new housing and business?

So how do you go out and find stories?

Oh God, I just like talking to people. One of the joys about making a piece associated with a location is walking through it and digging the stories up. It makes you aware of just how alive places are, with all of these untapped stories.

This big HW here was painted on by Coca Cola for the Olympics. They commissioned graffiti artists to make it, but none of the artists were from this area. On the opening night, loads of local graffiti artists snuck in and sprayed the whole thing. It's little vignettes like that that really make the place.

Let’s talk a bit about your background - how did you start to work on these radio pieces?

I was a musician. Then I was a journalist for the first ten years of my working life. Then I got to a point where those two strands merged into one thing, really.

That background helps me to capture the sound, and then use it - making music, but also using the ambient sounds: all the things that give a sense of place and a sense of atmosphere. When you're making audio, those things can be really messy, and interrupt you. But they're also brilliant for entering the imagination, helping people be transported to the places where stories happen.

With radio, you've got two really big advantages. One is the imagination, and two is the intimacy that you have through being in somebody's ear. You can connect with people in a more direct and personal way. That's the reason why I make radio, and why I stopped writing: the intimacy.

What do you think the role of sound is in narratives?

It's an incredibly emotional thing. It’s also a form of punctuation in audio storytelling. You can start a story off with emotion; it can bring things to a complete halt; it can create a sense of chaos and confusion. The whole time you're telling a story you should be playing with people's emotions, or perhaps not playing with them, but thinking about them.

What's interesting about some of your pieces is that they don't necessarily follow a very classic linear narrative structure.

I'm not a narrative master. I'm still very much a student of different narrative forms, but there are so many different ways to tell a story. You can create surprise in a story that doesn't necessarily have any in it, if you surprise people with the structure.

What’s your process for figuring out what the structure will be?

I break an interview down into themes, and I structure those themes into a narrative arc. And then I cut together the voices. I usually work with music underneath, because music has its own rhythms and that really helps when you're trying to work out the cadence of how somebody talks. Even if you don't end up using the music, which is often the case, having it underneath when you're cutting it just helps.

Then, I'll go to a place and record sounds, and transcribe those sounds to work out what I've got: things that are really close to the microphone, things that are far away and dreamier, general hums in the background. The important thing is not to just use them in a lazy, wishy-washy way, but to be really specific and targeted with them.

Let’s talk about the beauty of sound and its ability to reveal hidden histories.

Can you tell about how this works in the geo-located tours that you've been working on?

The geeky term is psychogeography. It's using location as a tool in your narrative. The stories are triggered by GPS: the company I’m working with, Detour, has amazing software that enables you to hear stories specifically when you're in one place. That’s a cool toy for psycho-geography, and for location storytelling.

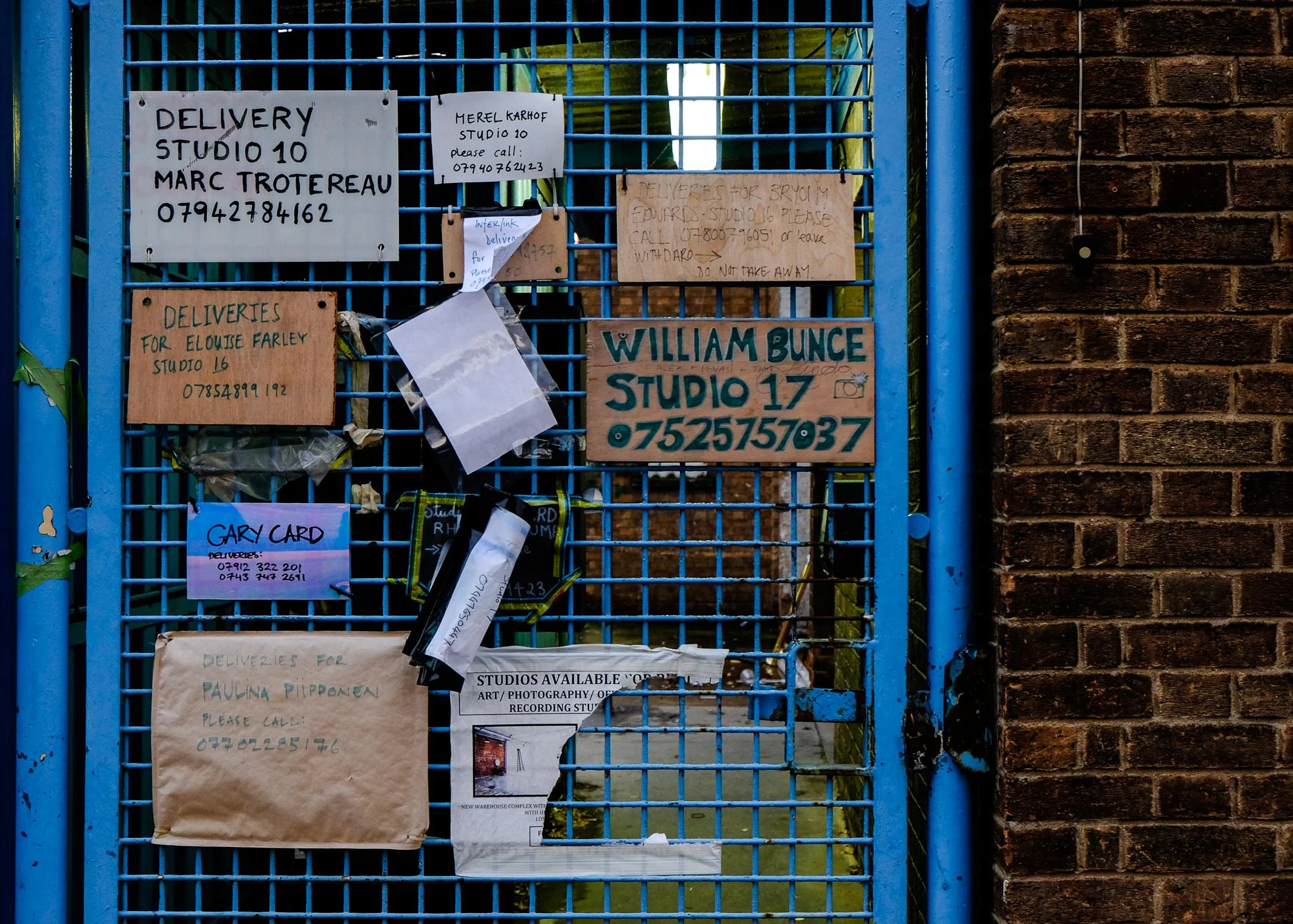

You can take somebody to a yard like this and say there's a lot of makers around here, and that's cool to know but when you're looking around it feels a bit generic.

But if you point people to that window in there, that's where they shave down wood to make tiki lounges, and in there, right now are two guys making lounges that end up in bars all around the world.

As soon as you take someone into that specific window or through a door, breaking it down into small parts, you have much a bigger impact.

Do you think placemakers can use audio as a different way to listen rather than look?

Listening to a place is not something that people necessarily think about but it’s very evocative and most places have unique sounds when you stop and listen. That’s about trying to feel what you hear around you, but also the sounds of the people. All you see are warehouses and this place can be intimidating if you don’t know where you are, especially at night. The reality is this thriving community of people who have lives, hopes and dreams — universal things that we all have. The ability to get people in there to hear about that, that's such a fun part of my job.

The narrator for the walk is a guy called Will Chamberlain. He was a fourth generation corporate lawyer who hated his job. He came to Hackney Wick and was so inspired by the art scene that he found here, he quit, and dedicated his life to helping the artist community.

He formed an organisation called Creative Wick, which aimed to be a meeting place for artists and developers, so the developers can include the artists in their plans, and the artists can speak to the developers in a language that they understand. His advantage in coming from a corporate law background is that he really is able to talk to the developers in a way that maybe the artists weren't.

He was involved in winning the Olympic bid. So he's really seen it change, and dedicated his life to making sure that change happens in a positive way. That's one cool story.

Is there an element of preservation in it - wanting to preserve these stories?

—

When you find a really good story, you have a sudden panic: you can’t let it get away.

—

Once I get the audio, I'm relaxed. It’s probably a selfish thing: wanting to be the one who does it, wanting to map that story!

How do you deal with conflict in your stories, if it's not always a happy narrative?

You have to be really careful. The biggest risk is messing with other people, like telling a story that would shame or hurt somebody. I'm confident about not getting the story wrong, because I only edit to help them tell their story. I would never put words in their mouth.

But you have to be aware of the impact of the story that you tell on other people. In a place like this, there's the artist community, and you don't want to exploit their woe as they're all pushed out. I don't want to sell misery. I want to make something that helps form a narrative - an idea of the place, so that it can be protected.

How can this approach influence placemaking?

You're creating empathy, right? By untapping all these hidden stories and locations, you're creating this sense of caring for a place. You're encouraging people to look at places more closely and more deeply and have more of a connection with them. It’s a sense of emotional investment. I imagine that's what placemakers want, although never having been one, I don't know!

—

Listening to a place and its sounds is not something that people necessarily think about. But sound is very evocative. Most places have unique sounds when you stop and listen.

—

If you had one piece of advice to people who wanted to use audio to make better places, what would it be?

Radio is super intimate, and you create an intimacy that you don't create with pretty much any other medium. So it should definitely be considered as a story-telling technique by anybody who wants to create a sense of place.

Audio is really effective and it's not expensive. It’s about skill. Find somebody who knows how to use it. With this podcasting boom at the moment it would be very tempting to think, "Well, anybody can do it, there's no skill in it." You can probably make something that, on first listen would sound fine, but all those impactful things I was talking about earlier - they're skills that need to be executed. Use it wisely because it can be an amazing thing.

As we walk around, David points out highlights from some of the stories

How is this spot connected to the story you’ve been telling us about Hackney Wick?

That whole tension is even more concentrated. We've just come over a bridge and here on the left there's another one. The local authority want to knock down those warehouses over there only to build another bridge. It's totally unnecessary, and it's the kind of thing that really riles the community here. People sitting round a table acting rationally will be able to talk about that in a constructive way. But sometimes it can just be bickering, two communities that can't stand each other.

—

You need facilitators who can speak both sets of languages. People who can stand between different communities are really crucial conduits for reason.

—

Do you think that there could be a way to embed some of the sounds that you create in the environment - so it's not just something that you're listening to on your phone but part of the new soundscape?

That's a cool idea. You don't want people to hear the same things over and over again because they'll go mad. But I think people want to know about where they live. They want to know the stories of the lives that were lived there before. Especially when they have visitors and friends and family come to stay - they really want to share those stories with them.

It could be seen as an impenetrable place here, in the sense that the warehouses aren’t open architecturally, so it’s important to bring out a bit of humanity.

It does seem quite impenetrable. But the artist and maker community have been so welcoming to me. Everyone talked to me. It's not just hipster artists. They're normal people living normal lives and they've got some great stories.

I think the developers need to work more in tandem with the community, just in terms of keeping them informed about what they're doing. The artist community around here that I've talked to, are not like, "Oh, I don't want any change. Change is bad."

It's that if your neighbourhood changes, you want to be involved and you want to feel like you know what's going on. It's very human that people will be riled by that, a bit confused and divisions are created. Incorporating people in what you're doing, and giving them a sense that you’re open to knowing them and they can get to know you, is really important. And one way of doing that is through audio - but actually, just meeting people. It's the best way.

Learning from David's Approach

LISTENING IN

Often the realm of architects and developers, it’s no great surprise that placemaking is dominated by visual language. And yet audio can be infinitely more powerful in communicating a sense of place and a vision of the future than a CGI. Tapping the imagination, and with the intimacy of ‘having your ear’ radio kickstarts a conversation with those that live there that brings a neighbourhood to life. So how can we use audio as an artform to make better places?

Making radio as a means of meeting people

The mere process of making radio encourages you to talk to people, listen more intently to the qualities of a neighbourhood, and opening up untapped stories. Walking around Hackney Wick, the graffiti on the walls and warehouses speak for themselves. But in areas where the community appears ‘invisible’ or thrives only behind closed doors, audio can have huge impact in elevating the social and cultural value of a place. David’s latest piece in Dagenham is being used as inspiration for an urban design team, to give them a flavour of the life stories of the place. Likewise, if a community or developer don’t have the time or access to engage, audio can become an icebreaker.

Seeking high stakes

High stakes keep us hooked. It seems counter-intuitive to seek conflict, but a story with consequences can move people to action and to take responsibility. When a place is divided along stakeholder lines, the audio piece itself can become a facilitator and impact future political decisions — balancing arguments from either side and encouraging both to listen. As in all forms of journalism, a killer narrative also elevates the story beyond local levels to highlight its place among national or international agendas (as in the case of Hackney Wick). And when a place becomes a symbol for a particular cause, the world takes notice.

Want more?...

The Hackney Wick audio walk launches shortly through Detour and Airbnb

Hear more of David’s work with Phantom productions or The Guardian

And catch his new series Voices, about to launch on Audible which captures stories from different voices around the UK and across the globe.

Follow him on twitter to stay up to date with what he's recording.