'Why are you doing it? And if you stop doing it, would anybody care?'

Brand strategist Jane Wentworth on asking life’s biggest questions of cultural institutions

8 minute read / Rosanna Vitiello

Jane Wentworth cuts swathes through culture. As an expert in branding for the cultural sector she’s guided institutions as diverse as the V&A, The City of London Corporation and the Smithsonian to understand life’s biggest questions: who are you? Why do you exist? And if you stop doing it would anybody care? Focusing on such fundamentals is no mean feat, but Jane’s quick wit and strategic vision means she’s able to bypass politics, shine a light through the dust and help cultural institutions clearly see the value of their place in the world. How do you approach such a glorious but gargantuan task? The best training for brand strategy is life, and Jane’s patchwork career path has encouraged her to see different cultures from all angles. From this she’s established that while the secret of a good cultural brand starts with listening, it only works when the people you talk to take control of their own story, and mark their own path. So we met at the Barbican to take a cultural trajectory through the City of London. Here’s the one and only, Jane Wentworth…

Jane, you specialise in cultural branding - let’s get one thing straight before we start, how do you define it?

Cultural branding has two definitions. One is brand strategy - and all the lessons learned from brand - applied to the cultural sector. The other definition is that culture is part of brand, the culture creates it. For instance, the Barbican brand is about the culture of the Barbican, as a residential complex but also as a place that is a cultural entity in itself.

I think brand starts from inside the organisation.

—

However brilliant an advertising or PR campaign, however clever the stories are, if the real truth of the brand doesn’t come from within the organisation, it hasn’t really got any legs.

—

How did you get into working in cultural branding?

I’ve always been interested in signs and signals of identity, in the labels on things and what they say about the person or the institution. Even as a child, I was always looking at people thinking, "Why does she wear those shoes? What does this jacket mean?”. That has been an obsession of mine, as far back as I can remember.

It led me into going to art school, which I think is one of the best educations you can have, because you learn history, psychology, storytelling, you learn to be sceptical. And you meet all sorts of people who are not, in inverted commas, terribly clever academically, but they have other qualities. I studied illustration and then textile design, and when I left college I took a job in Paris for a forecasting agency called Mafia who were creating the trends of the future. Not so much ‘this season is all about frills or leather’ - it’s much bigger picture, more strategic.

But my first lesson in branding came later, when I was working for a shop called Mr Freedom owned by the fashion provocateur Tommy Roberts. I had designed a range of print textiles for them and when a sample came back it said, “designed by Mr Freedom”. I said to Tommy, “It was designed by me. I want my name on there”. He said, “Look, ducks, you need to learn something. I'm the brand, you just do what I pay you to do”. It was an enlightening moment because I thought, well, yes - nobody knows who the hell I am. If I have fabric that is being produced with his name on it, it will be recognised and much better for me.

That led me to be an independent textile designer and starting a fashion business. Putting together fashion shows, you have to picture the whole story. You have to imagine the person who's going to be wearing it. I liked the holistic nature of it and I learned most of what I know about business on the job – production, sales, marketing, distribution, PR – the lot. But when the fashion business eventually wound up, I got a temporary job at Wolff Olins (the brand consultants) and stayed for 18 years. I went from being a jack of all trades to becoming a strategy consultant. But it was a pretty long and wavy path.

What did you pick up along the way?

I recognised that branding in the commercial world is really not much different from fashion. It's corporate fashion. You're thinking about all the same things as you do when you're designing a collection.

—

Who is it for? What are the values? What's the personality? What's the attitude you're trying to express and how do you market it?

—

At Wolff Olins I worked for all sorts of clients, from salt mines in Siberia, to airlines, to hotels. Towards the end of my time there, we started working with cultural institutions, including Tate Modern, which was launched in 1999. I suddenly thought, "this is what I want to do." I realised there was a huge gap in the market for affordable brand strategy within the cultural sector.

So the field of cultural branding wasn’t well-defined when you started - why do you think it caught on?

Everyone saw how Tate had completely changed the landscape. Nobody had thought about branding museums or opera companies with the same rigour as you would brand a mobile phone company or a bank. Everybody in the world was talking about Tate had done.

What's your discovery process? How do you attempt to understand what the meaning of the institution is?

This is not going to come as a surprise, but it's absolutely about getting inside the organisation. Talking to people, listening to people. Sometimes, the clue comes at the last moment. You've been talking to somebody for an hour, then just as you're leaving, they'll let something drop - and that's the killer perception.

I know nothing about archaeology; but I love the moment when they brush the dirt away and you suddenly see a dinosaur bone or a shard of pottery. I feel what we do is a bit like that.

—

It's brushing away all the stuff that's getting in the way and clouding people's sense of what they passionately care about.

—

People being protective of their territory, sometimes being disrespectful of other people's role in the bigger picture.

You’ve got to find the thing that everybody wants to achieve. If you care about your subject, you can’t waste time being competitive with each other about how you do it. That’s where you start to develop the brand strategy and ultimately the essential narrative or the story. It shouldn’t be more than a hundred words long, but it’s the essence of all communications.

When there’s so much existing culture and history to an organisation, how do you distill it down?

The end of the first phase is the analysis. You do desk research, looking at their business and marketing plans; you look at their competitors; at the audiences and see where the gaps might be. There’s also research that’s talking to people face to face. Then you analyse it all and say to the client, “Well, here you are, right now you’re great at this, or you’re crap at that. If you don’t get your act together this is going to be a big problem. But if you do get it together this could be a big opportunity.”

The second phase is getting everybody together to paint a picture of what success would look like. And asking those really fundamental questions: what do you do that is special? How do you do it? What are your values and what do you believe in? What kind of people do you want to work with, and what do you expect of each other?

—

Most importantly of all, why are you doing it? If you stop doing it, would anybody care?

—

How does narrative help with that?

It gives everyone in the organisation a shared sense of the future. What does success look like? What’s stopping you from getting there?

For instance, if you want everybody to be able to appreciate opera, what’s getting in the way? Well, an opera can be four hours long, and you have to sit still, and sometimes the stories are really silly. But if you make it real and relevant to somebody’s life, then people have a way in. If you present an opera like La Traviata, which is all about love and loyalty and death, in a language that people can understand, they can relate it to their own experience.

Branding has a reputation - possibly undeservedly - for stamping things with the same message again and again. How do you look for originality?

That is exactly the problem: many people are sceptical about branding because they think it’s imposed from the outside. That it’s phony, that it’s just marketing hype, not built on anything authentic.

—

Place branding is often seen as just imposing an idea that’s already a success: “Let’s just make another Shoreditch.” It’s tempting to do that.

—

I live just off Caledonian Road, which has resisted being gentrified for the 30 years I’ve lived here. Someone decided to paint its nickname “The Cally” on a bridge – but it didn’t change much.

I think branding a place can be useful for a number of reasons. It can help business, it can help attract funding, it can help give people a sense of community. But it has to come from within. You can’t have a lot of creative types sitting around thinking, “I think we’ll make them like that.” You have to go in and say, “What are you like? How can we help you express what makes you unique?”

It’s the same in institutions. You can’t just say, “Let’s turn the V&A into another Tate Modern,” because that never would have worked.

What do you think placemaking can learn from cultural brands?

Branding needs to be truthful and authentic. It needs to be distinctive, it needs to be holistic, because it’s not just about logo.

—

You’ve got to really think about the whole experience: what does it feel like and how does it talk?

—

For instance one thing we often have to deal with in cultural institutions is the tension between content and how to communicate it. Curators often think that the marketing people are dumbing things down, trivialising their work. The public engagement people get incredibly frustrated because they think that the scholars are just talking to their own peer group and ignoring the public.

That’s tough. It's a very difficult thing to resolve and I’ve spent a lot of time trying to do exactly that. That’s why it so important they all share a sense of the ultimate purpose of what they do.

Is it also tricky in terms of control and ownership, and whose voices you listen to?

Control is an interesting issue. Some brands, like Apple, are tightly controlled. Everybody who works for Apple has the Apple brand in their own DNA. And you do need to control every detail of the brand if you want to be coherent. A lot of people hate that, and find it spooky, and I can see why.

—

But you control the brand by empowering people to make the right decisions.

—

That's why having a clear brand strategy is so important. Everybody needs to contribute to building it - that doesn't just mean the management team, it means everybody from the security guards to the people at the front desk and all those other people who never get seen by the public, the technicians and the researchers. If these people are involved in creating the brand, they own it. They have the confidence to make the decisions that are concurrent with the brand.

How important is the physical building in a cultural brand?

So few organisations think about the brand early in their planning cycle. They might want to create a fantastic new museum or concert hall. They’re focused on raising a huge sum of money but often don’t have a clear idea about why they’re doing it.

The work we’re doing here for the City of London Cultural Hub is about creating a sense of place. It's not a secret to say that the four cultural partners - The Barbican, Museum of London, LSO and Guildhall School of Music and Drama - want to create a cultural destination. That's what we've been doing with them for the last year. Not surprisingly, they all had slightly different ideas about what that vision looks like. But by involving everyone in imagining what the place should feel like, we’ve created a story that’s about animating the spaces in between the different institutions... but I can't show you yet!

Do you think that there's a capacity for cultural branding to be elevated beyond just an individual institution or district - can it give a city an identity?

I think that's exactly why the City of London Corporation is interested in this project. The City, or Square Mile as it’s known, is one of the most important financial centres in the world, but Brexit might present a threat. I know it's already happening, that banks are closing down their London offices and people are going back to Zurich or Frankfurt. Culture can make London much more attractive alternative place to work. If you can make it about a complete holistic cultural experience, not just glossy buildings with lots of money and big bonuses, you’re creating a story that’s about culture and commerce and history.

And The Mayor of London is also supportive of culture's role in regeneration as well. Do you think that there will be a melding of place branding with cultural branding?

I hardly draw a distinction between them. I was on the board of the Liverpool Biennial for a long time and I do think that the Biennial played a huge role in the regeneration of the city as a cultural destination. It took a while to build up, but it brought huge numbers of people in to the city. Manchester is also flying at the moment, as the nucleus of the Northern Powerhouse. I never thought I would say it, but George Osborne has done a lot for culture – he’s a real enthusiast.

Beyond the UK, you've worked a lot internationally. Do you see any key differences?

The obvious one is that different cultures have different ways of doing things and they have different attitudes to culture. For example in the USA there’s very little public funding for the arts whereas in Europe, culture is heavily subsidised.

Working in Scandinavia is interesting, because their museums have been used to being heavily subsidised by the government. They weren’t too worried about visitor numbers. But now that governments there shifting strongly to the right, the mood is changing and cultural institutions are realising that they've got to be more entrepreneurial. They've got to think more about the audience, to make more imaginative use of their content in order to have better shops, better cafes, sell more, charge for more. And they are recognising that they have to take their brands more seriously.

So at the end of the process, how do you hand over the story to the organisation?

Once you've got to that point where you've got the brand strategy, the real work has to start, which is actually changing the attitudes of the staff.

—

More and more of our work now is in what we call the internal engagement, or living the brand. Once the brand strategy is established.

—

We go back every couple of months and do workshops with the staff to ask, "How's it going? Are you living the values? Which ones are the easy ones to deliver and which are the tough ones?"

For instance, let’s say one of the values is generous. And then you ask, “What does that really mean? Give me examples of generosity that you've experienced in your work (or not!)."

It's like a diet. Someone says "I wish I was a size eight," but happily keeps stuffing themselves with McDonalds and fries. They want things to be different, but they're not prepared to make the changes that will make those things a reality. You can’t have the things you want if you're not prepared to get fit.

On this note, we tack across the City of London, where Jane has worked for many years, to explore places, stories and brands.

Places aren’t just sites to Jane, they mean something. Taking a 1000m trajectory from the bulk of the Barbican to the edge of Smithfield meat market, every spot she points out holds story or symbolism. While each has influenced her, together they make up the fabric of the city — a narrative she’s woven together on both a professional and a personal level. On the formal side uniting the neighbours that are the Guildhall School, LSO, the Barbican and the Museum of London under one brand. On a more intimate level, Smithfield yields savoury memories of bacon sandwiches while working as a student at the old Dewhurst Wholesale Butchers — “I wasn’t even a typist, I only made it to the post room:” and close by sits the place she and her husband Richard squeezed their guest into for their wedding party, now earmarked as the site of the new Museum of London.

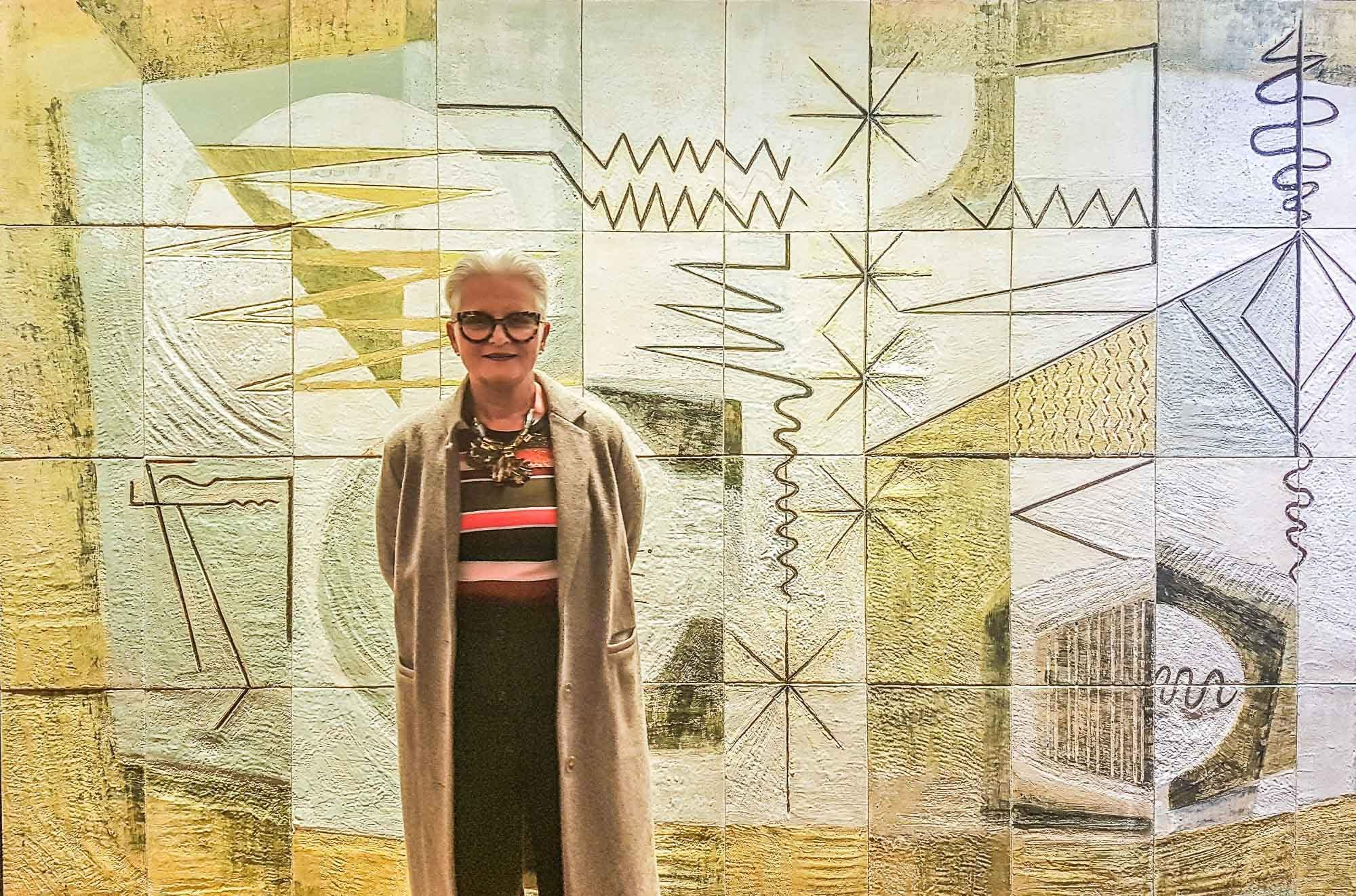

On layers of old and new Dorothy Annan’s 1960's murals have been grafted from the nearby telephone exchange — set for demolition on Farringdon Street — to the passageways of the Barbican. Still strikingly modern, resilience in the face of change makes a place stand out with powerful character.

On the idiosyncratic among the organization Barbican Chimes Music Store is the Guildhall School of Music’s quirky neighbour: “it’s old-fashioned and the people in there are sweet. Nobody goes to music shops anymore. But they’ve got sheet music in there, and ukeleles…it’s a complete anachronism. I love it.”

On putting your best face forward The Barbican was built like a citadel for culture, which is in fact its original logo. Take a walk down Beech Street underpass, and the message moves from 'dry riser inlets' to 'danger of death'. “Here’s a treat for you," says Jane "In there, there are world-class performers and actors…and outside it’s filthy!” But attitudes are changing — the underpass is going to be refurbished with the idea to make it into more of a pedestrian space, with shops and cafes. Likewise, the Museum of London is moving from it's insular roundabout building to a more open site that integrates with public life at Smithfield. The City is opening up.

On convention The window boxes at the Barbican reveal a brand’s subtle governance of a place — “You play by the rules here" says Jane wryly…"In the Summer, I think the only colour you're allowed is red geraniums…and you're not allowed to put unseemly stuff there. It’s all part of the good taste Barbican brand.”

On pattern Ask Jane how she sees her surroundings and her answer comes quick: “I see the world in patterns,” she explains, drawing our attention to an embellishment on a nearby building. The design, the colour and symmetry stand out - an interest that stems from her background in textile design but has parallels in branding — boldness, repetition and originality are integral to both.

On signs and memories: on the site of the new Museum of London sits a small relic with real character — a sign to Bubb's restaurant: “We had our wedding party here. It closed down about 25 yrs ago. It was a popular and gorgeous French restaurant for a while. When we got married they only had room for 19 people at the table, so some had to sit at the bar and we had everybody moving around after each course. Richard keeps saying he’s going to come and steal the sign.” If it’s gone, we know where it is.

On building new places: “If you do what we’re doing now, taking the time to walk around and look, you’d get a fantastic response from people. One of the reasons I’m not a huge fan of market research is that it doesn’t open up anyone’s thinking." But take this approach and you might start to redefine a place based on the remnants of culture the city lays before you.

Learning from Jane’s Approach

WEARING IT WELL

The tussle between control and expression is most marked when branding a place and a culture. Ultimately, both are a collection of personal stories, symbols and experiences set within a space, from which we divine a brand’s character and values. Such a collection needs structure to tie them together — a common motif, a house style if you will. While that forms the thread of narrative, it’s essential to give it ‘a bit of flex’ as Jane puts it — the originality and idiosyncrasy that attract us to great cultural places. Because there’s no room for beige in Jane’s world.

Empowering from the inside out

People don’t believe in branding because they think it’s imposed from the outside. So build from within in a way that everybody contributes. That ties people to a place. If you’ve been a part of identifying that narrative, then there's no reason why it shouldn’t be something you follow through with — the story becomes yours, and you become the storyteller.

Brands don’t live on paper, they live in people

Cultural change takes time. Getting the strategy down on paper is just the first part, so allow for the extra legwork. Once you have that run workshops to communicate the values of a culture, keep it simple so everyone can hold the story in their head. And most importantly go back to talk to those using the strategy and find out how it’s going. Some people find it hard to talk in abstract values, but ask for anecdotes and examples of how those are being lived and the people that make a place will become more conscious of the changes they’re making in their culture.

Want more?...

Follow the work of Jane and her associates at JWA and stay up to date on twitter

Keep an eye out for the cultural brand for the City of London Corporation to be launched this Summer.