‘I've trained myself to see things that other people aren't aware of. You start to see a secret writing and a different language.’

Photographer and artist Anthony Gerace on finding a language for landscapes the world long forgot

8 minute read / Nastasia Bassil & Fanny Agren

“There is something gross when you think about old magazines. It’s just paper rotting. I love the smell.’’

You wouldn’t think that this was an artist describing his medium - but photographer and collage artist Anthony Gerace asks us to look again at the things most of us pay no attention to - and that includes places. Anthony’s work sharpens our gaze upon the emotional and social resonance of landscape, and makes art out of a world that is collapsing, weathered or hidden. Pictures of trash cans, the alleyways that run behind Toronto’s houses, dusty signs among the deserts of California. He’s a photographer with an uncompromising and uniquely powerful sense of place, casting himself (by his own account) at the mercy of landscapes ranging from the vast Nevada desert, the arid high peaks of the Alps, and the pastel weatherboards of American suburban homes. He’s completed commissions along this journey for the New York Times and photographed French graphic designer Jean Jullien before his ‘Peace for Paris’ illustration became the symbol of the response to the Paris attacks in 2015. His current project is the preparation of his first book of collected collages, due for publication in June 2017.

Local Legends talked to Anthony on a spring Saturday morning to find out how he captures the things we don’t see in his photos, how places surprise him, and why collecting the past is leading us towards the next Dark Ages.

Anthony, how did you start looking for stories among landscapes?

When I was in Toronto, I was really engaged in my studio production shoot practice, until I went outside and started photographing the same people in different spaces in the city. It led me to this network of alleyways in the city, where you can go from one end of Toronto to the other through an alleyway system without seeing any part of the city that you would normally see. You're seeing the backs of houses and garages. They’re very stark, almost like a patchwork.

That got me thinking about how those spaces define the city as much as any space that you would get through via public transit or main walking routes. I realised that they were equally important and equally deserving of my time as a photographer and image-maker.

I've trained myself to see things that maybe other people aren't aware of. My girlfriend makes fun of me for taking photos of garbage all the time. But I think that really speaks a lot to the culture: garbage and refuse, things that people pass by and don't pay attention to. You start to see a secret writing and a different language.

What stories do photographs tell about place that people don’t - or can’t - tell?

I think that by looking at weathered objects and buildings, you get a different sense of what that place is than if you were to go and interview the people who live there. American landscapes are a good example of that. For the last projects that I did in the desert, in California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico, we went to 50 or 60 different towns. You start to see these typologies and indexical signs of how these spaces are used. For example, if you take somewhere like Savannah, Georgia, the architecture really reflects the personalities of the people who live in those spaces.

—

You see signs of life even though there's no one in the images.That's what I'm looking for with my photographs.

—

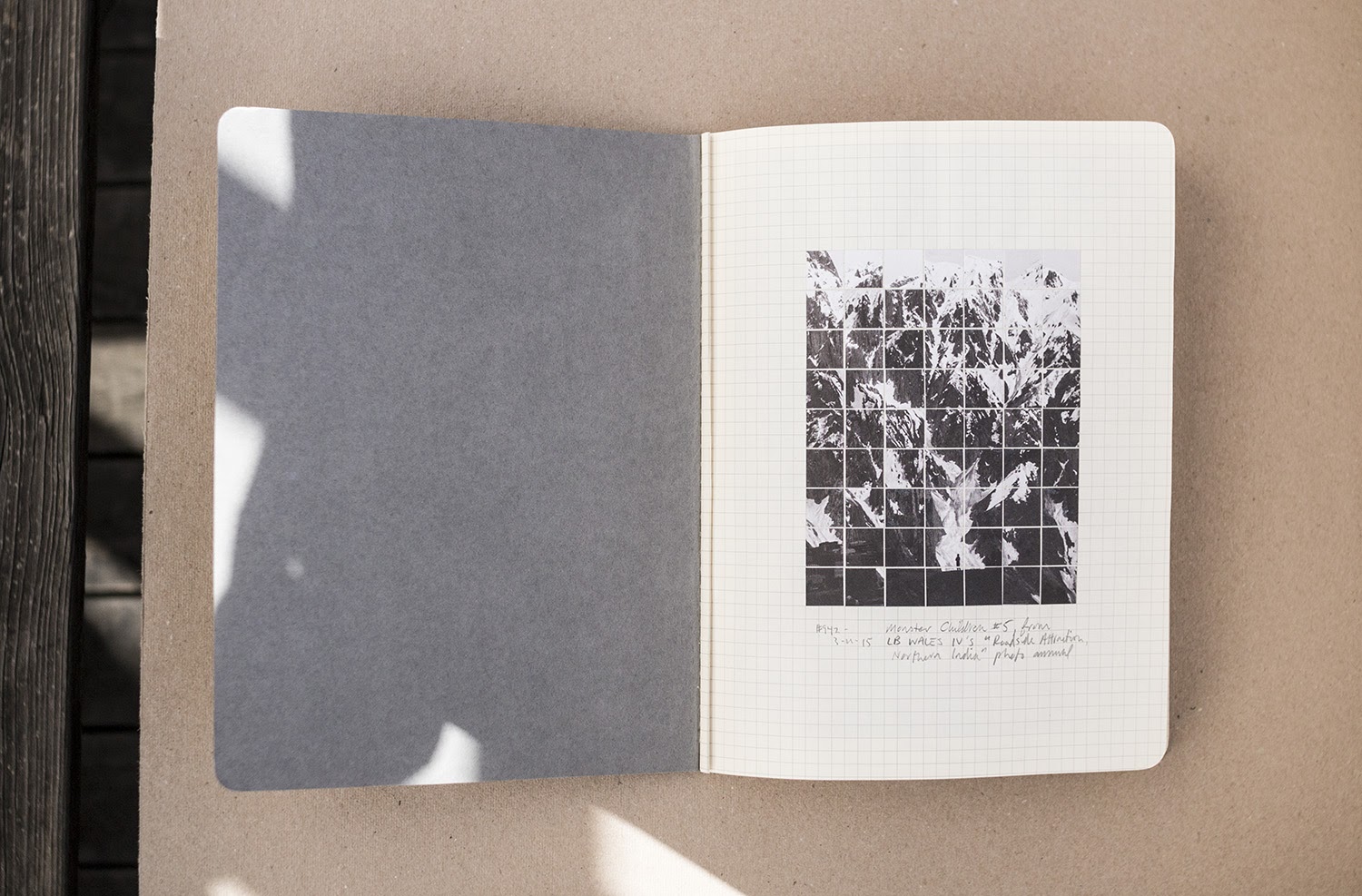

As well as your photo series in the desert, you’ve also worked recently in the Alps. How do those two experiences of very different places compare?

I got a commission from The Criterion Collection, which is an amazing archival collector’s film service, to take photos for the movie 45 Years. They sent me to the highest peak in Switzerland, Jungfraujoch, which is 6,000 metres above sea level. I thought I knew what I was getting into. I did not! It was three times higher than I’ve ever been. It was insane.

But in a lot of ways, it was exactly like being in the desert. It was the inverse in terms of climate, but it was the same aridity, the same emptiness, the same alienness. It had the same sense of danger as when you're in the high desert of California. Those places are dangerous. If you run out of gas, you’re in trouble.

I had the same sense of the mountain town as I had of the desert town: totally subservient to the landscape that surrounded it. But the locals had a blind spot for the magnitude of the landscape. They were like, "Oh, it's just the desert". It was the same thing in the Alps: "Oh yes, it's a mountain." It's so interesting. My experience of these places is totally defined by my lack of experience in them.

If I’m photographing London, or LA, or Toronto, where I do feel like I have an understanding of the city, it’s different. You have to be in a place long enough to be able to willfully break down that understanding and look at it. You can never really understand the place. It's what make places so amazing.

Your work has also included people, as well as landscapes. Do you feel there are similarities in your approach to the two subjects?

Yes. The longer I’ve been making work, the more I've stopped seeing images as representational and the more I see them as objects in themselves. An image of a person can become as grandiose as an image of a mountain, because they're both flat representations of experienced things. The further away you get from the act of making the image, the more detached the image becomes. One of the nice things about cutting up images and working with its structures is that you start to see those connections.

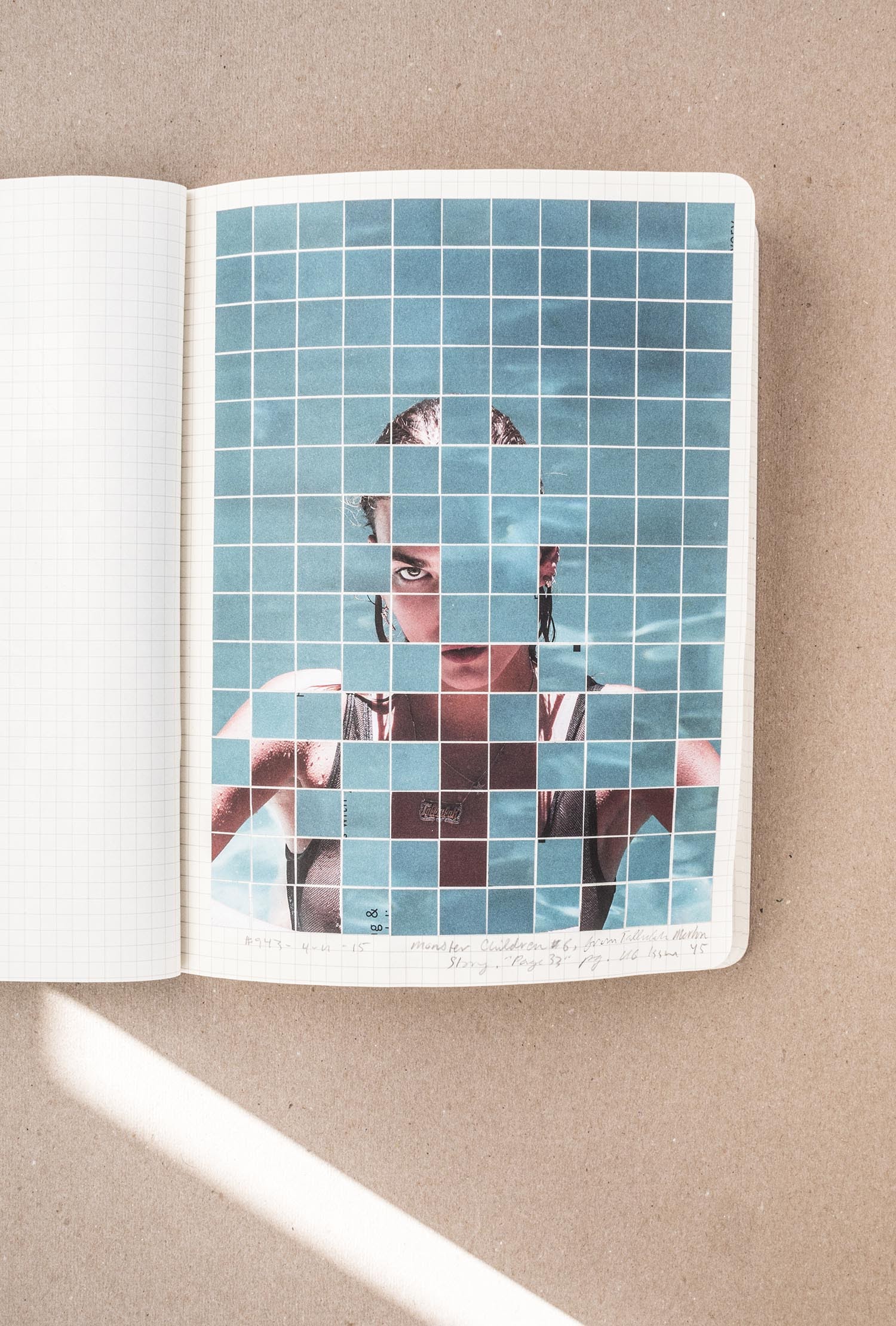

Tell us about your collage work, which is also a major part of your practice. You’ve been approached by Ain’t No Editions to publish a book of your collages?

Yes - it's seven years worth of work in 128 pages! Every photo series that I've done has had the intention of being a book with a narrative. I'm very interested in the idea of narratives and how narratives are constructed. I started seeing this collage book more as a piece in of itself, so that it functions less like a book and more as a collage that you engage with over time.

The image in the first piece in the book is a photograph that I took in 2012 of a friend of mine. It was used as the poster for my first solo show. That work is literally collaged on top of in the book by another collage as you turn the page. Then you turn the page a third time and the title is placed on top of those two images. Taking an image that was very meaningful to me, effectively destroying it, and then placing the most successful image that I’ve made on top is a very weighted set of gestures. It’s as succinct a mission statement as I can make, without being prescriptive in the way the work is read. It says that I’m not precious about what those images mean.

Do you see similarities between the collages you do and the way places are constructed?

When I’m making a collage, I don’t know what it’s going to be when I’m making it. It surprises me once it’s completed. There’s also something interesting to me about the fact that I could be taking an image from the 1940s, a piece of advertising copy from the 1950s, and something else from the 1960s and layering them all on top of each other. It is effectively three different realities compressed into a single plane. You can almost read it as history being compressed on top of itself.

In the same way, medieval architecture is almost unintentional. The cathedrals that were built over 100 or 200 years - the person who finished building it is engaging with it in a different way than the person who designed it was. There's a conversation happening in real time, in the architecture. I think that exists on a smaller scale, in the way that a neighbourhood is created or that buildings engage with each other. London is a great place to see that happening: you can see traces of Victorian England next to the new builds from the '50s and '60s. You can see the way things were cut, or torn, or displaced.

I love going through my day to day life taking pictures of these ‘city collages’ that exist almost accidentally. It’s like postering: you can trace the timeline. The top layer is the most recent; the bottom layer is the oldest.

It’s visible layered history, in the same way that collage is.

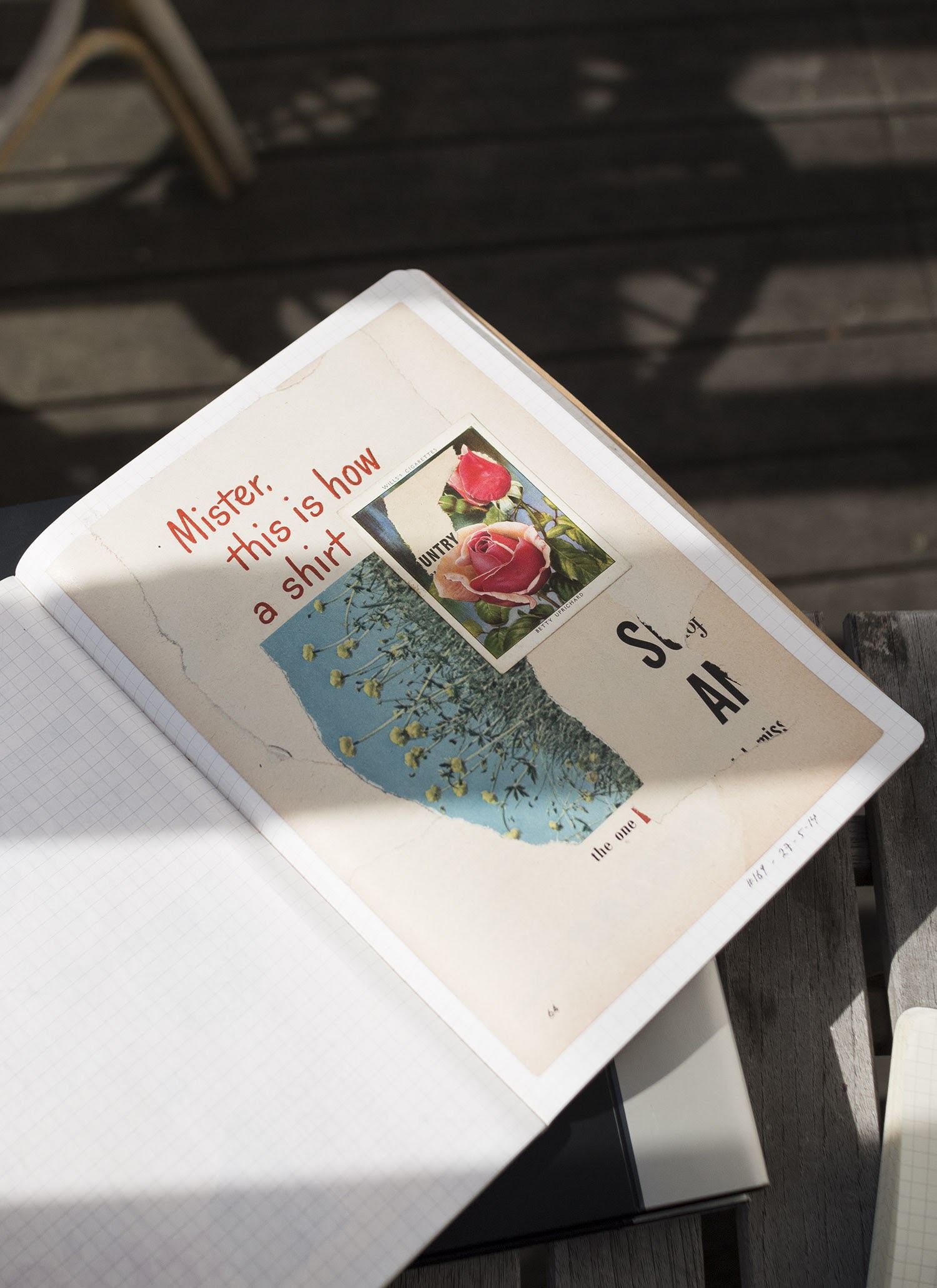

Yes - although the thing about collage is that, while it is a very old practice,

—

I'm actively trying to re-contextualise language rather than pay homage to any particular history. Everything that I work with is garbage.

—

I would love to stress that. These magazines are garbage. They say nothing. They were designed to sell ads. There's no ‘history’ in these objects. Their history is entirely in their substance and in their more meaningless parts.

So many people confuse collecting antiques with being historians. Antiques are not history. What they represent transcends the object itself and gets talked about by people who are not collectors. I think collecting is the biggest waste of time. I will - full disclosure! - describe myself in some respects as a collector, as much as I hate myself for it. I have a record collection and I buy books. We have in some ways let ourselves down a blind alley, because collecting is so prevalent in our culture now, but in some ways it prevents new ideas from happening.

Becoming complacent about where you came from is the easiest way to stagnation. The Dark Ages was a period when things were happening but there were just no records. We have the potential for a new ‘Dark Age’ right now, because people are obsessed with the past, myself included. Contemporary experiences, digital experiences, are not given the same weight. This is coming from someone who makes collages. I know!

Does where you are - the place you’re in at the time you’re creating - influence your collages?

In very weird ways. One of them is the source material I have access to. When I was in Canada, I had a dark room, I had a studio, I had a scanner, and things that I could use and fall back on easily. I moved to London and I lost all of that. I no longer knew where to get source material. The source material I did find in the UK was vastly different. American magazines were more saturated, more colourful, while British magazines were more two-toned and the printing methods were different. You had immediately a very slight but very significant aesthetic shift.

In Canada, the relationship between the words and the figure in my collages was also a lot more precious. I don't mean precious as in a good way; I mean it in a very finicky way. When I moved to London I let go of that preciousness, and I started seeing linguistic connections that I wouldn't have seen before.

When you’re going to a place to shoot it, what’s your process for attempting to understand it? How do you find its story?

I embed myself and I try to get the full experience of it. There's a sense of wonder at play, to do with the fact that I'm going to places that I don't understand - and will never understand because I can't live in them.

I went to Japan last year and it was amazing to engage with urban spaces that were totally different than any I've engaged with before. One of the problems in living in a big city for long enough is that you fall back on what you know. The saving grace of my work has been these projects that take me out of my comfort zone: to the desert, to the mountains.

I’d love to live somewhere where I don't speak the language. I want to live somewhere where I am completely at mercy of the space that I'm in.

If you know the story of a place before you go there, does it affect how you approach it? When I photographed Box Elder [in the Utah desert, in 2015], I was drawn there by a story I had written for myself, in my own head. Looking back on it, in some ways I feel very naive about how I approached it. I didn't understand the American West at all. I didn't understand how big it was and how everything out there has some kind of history attached to it. I didn't understand what Robert Swiss' intentions were when he put the spiral jetty out there. The transcontinental railway could have ended anywhere; it just happened to end there.

These configurations of history are everywhere. You could throw a dart at a map and see an equal amount of historical intersections anywhere. But these striations of history exist in the desert because nothing is ever lost in the desert.

It made the project far more interesting. I was surprised by the place and I was much more receptive to it, viscerally, because of that.

When you’re taking pictures, are you trying to transmit a message that you have in mind? Or is it more intuitive?

When the photos are being taken, it's intuitive. I go looking for what affects me emotionally and aesthetically, and after I've done it for long enough, that feeling will translate into something artistically and visually viable. The actual artwork - not to sound pretentious! - comes in the editing: the drawing out of the images that I find meaningful. I start to infer meaning after the fact. When I went to Cornwall a couple of years ago, I shot constantly. I was just shooting anything. It wasn't until Brexit that those images started to make sense.

—

If you know what you want to get out of the work before you undertake it, you might as well just write an essay.

—

Box Elder taught me that I shouldn't go in with an intention. I should go in with a vague sketch of an idea and I should be open to surprise.

What do you think of the kinds of one-liners created by tourism or marketing corporations to describe places? Are they overly focused on transmitting a message?

I think those one-liners have to exist because they end up being a way into the past for the viewer. You walk through the Tube and you see advertisements; certain things catch your eye and certain things don't; but all of it is equally important because none of it says anything. Ten, twenty or seventy years from now, it will say everything. It will speak to what our culture valued, and how it was marketed to.

—

If you can define architecture as the longest-lasting commentary on an era, you can look at advertising as the shortest. The fact that they coexist simultaneously in the same space is crazy.

—

The American photographer, Walker Evans, who was active from the '30s to the '70s, was obsessed with advertising slogans and how those commented on this psychology of the culture. Even though it speaks to a society in the most crass, meaningless, effectively horrible way, that's perfect, because that shows what those marketers are thinking and it shows how we respond to it. There's a set of billboards outside of Euston station that's constantly getting updated. Every so often, they rip it off. And every time they do, there are unintentional poems up there.

So if you were to give one piece of advice on how to really look at a place, what would you say?

Go to the place and engage with it. Maybe that means going to different places and investing in them. I’m using the language of money, but I’m talking about people investing themselves and their lives in new places.